Over the past year, we partnered with a digital health company to develop a remote patient monitoring platform that could help older adults age in place. As part of our engagement, we conducted a series of design research studies to help us better understand the needs, pains, and context of older adults. The result of this UX design for seniors study helped inform the product’s design, development, and strategy. During an iterative process, from defining the MVP to launching the pilot, we learned valuable lessons worth sharing with other healthcare UX designers.

What is a design research study?

Design research studies help us learn how innovations and new approaches affect behavior and learning among target users. These studies provide a systematic approach to learning and provide users with realistic contexts so we can observe user behavior and gain insights that help inform the design process.

In developing research studies this past year for our client, CommuniCare Health, we had two overarching goals: to understand user context and to validate the product.

Who are our users, and what are they trying to do?

Understanding user context is key to developing a product that users love. To create an exceptional user experience, we needed to know the following:

- Understand what motivations, activities, and problems our users currently face

- Identify how users currently solve their problems

- Validate our audience’s process and decision-making regarding a move to independent living versus aging at home

- Recognize what technology our users currently use as an aid to their health needs

- Describe the pains and gains of the technology they currently use

- Describe the relationship between caregivers and seniors

Does the product we’ve designed help our target users address specific needs?

Failure to understand customer needs is one of the leading reasons for customer churn. In design research, it’s important to validate the product and prove that it can meet the needs of its users. To validate the product, we had to:

- Collect a mix of qualitative and quantitative data for future iterations and the next phase of product design and development

- Observe first impressions and reactions

- Test usability of the product, if the interface is intuitive, how users interact with the product, and its general accessibility

- Validate usage of the product in real time

- Measure engagement, gains, pains, future needs, and motivations

Design study methodology

Research methodology varies depending on what we want to learn and what’s available to us. For this particular study, we focused on four methodologies. Select any of the methodologies below for a summary of learnings and tips, or jump ahead for a deep dive into our whole process.

Our study consisted of three phases incorporating four methodologies. The graphic below shows the timeline and how we applied these methodologies in our user research and design for older adults.

User interviews – understanding context

In-person interviews are one of the most effective means for uncovering user needs and collecting qualitative data. In our engagement with CommuniCare, we kicked off our design research study with a series of in-person interviews to help us better understand the target user, the context in which they would use the product, and how users generally manage their healthcare needs. Here’s the information we needed to capture:

Interview learning objectives

- Define the user profile: what motivations, activities, and problems they currently face

- Identify how they are currently solving their health-related problems

- Recognize what technology or solutions they use to help them at home

- Describe the pains and gains of the solutions they currently use

- Describe their caregiver relationship

User interview methodology

We conducted more than 30 in-person interviews at each participant’s home. Each interview was one-on-one and lasted approximately 60 minutes. During the interviews, we asked participants about their daily routines, overall health, support, and care circles, relationship with technology, and current medical habits.

User interviews: What we learned

One-on-one interviews help us understand our participants’ natural activities and habits and the behaviors that participants might overlook when responding to group questions about their lives and technology use. Here are some learnings and tips we picked up during our face-to-face interviews with seniors.

- Set expectations

- Read the room

- Have clear goals

- Adjust the script

- Use visuals to broach sensitive subjects

- Conduct a daily debrief

Set expectations

Our interview process consisted primarily of contextual interviews. Contextual interviews are designed to provide insight into the context or environment in which a design will be used. A contextual interview typically combines a traditional user interview with observations of how a participant might use a product or service in the future.

Some of our participants had never experienced a contextual interview and didn’t understand the method and purpose of it. Because we were conducting interviews in participants’ homes, it was important to set expectations, and tell them the topics, the length of the interview, and how the interview results will be used. We’ve found it’s important to use clear and simple language. For example, instead of saying, we are design researchers conducting contextual interviews, we’ve found that participants were more relaxed with the following language:

We are part of the team that will be designing a product for you. But before we start the design, we need to gather information to make a product that would best suit your needs. I’m sure you may have questions. Feel free to ask us what you might be thinking.

Read the room and be flexible with your questions

When interacting with a new user group, be prepared to deviate from your script. For example, during the interviews, one of our participants was reluctant to engage and answer our questions. As the interview progressed, the participant became more anxious. To help him relax, we needed to deviate slightly from our script to better understand his concerns. This pause allowed him an opportunity to open up, at which point he shared with us that he considered himself tech-savvy. He went on to ask us if we incorrectly had identified him for this study. To put him at ease, we explained that his insights were as valuable to us as those of his non-technical peers. Then during our interview with him, we specifically asked him how he helped his peers when they experienced technical difficulties and how he felt tech products could better serve older adults. From then on, he became more open and collaborative, becoming one of our most helpful participants during the pilot and its studies.

While it’s important to have a script that outlines your interview goals, be prepared to pivot. If you sense that your users are uncomfortable with the questions you ask, alter your follow-up questions so you can better understand their hesitancy. Empathy is critical in user research and design for older adults.

Have a clear goal & anchor to all your questions

To ensure interview validity, it’s important to be consistent in your line of questioning and pose the same base set of questions to each participant. Avoid asking them random questions or trying to wing it. As mentioned earlier, sometimes your questions will receive short answers or your participants may digress. This is fine if you remember your anchor or your primary reason for conducting the interview. For example, in the case of the reluctant participant we described earlier, we followed our interview script, but we also integrated new questions that allowed us to gain his perspective on how others learn and use technology. A consistent interview approach will help you meet your objectives and goals.

Adjust your script as needed

Even after taking days to write the perfect script, some questions may not resonate with participants. Be aware of any questions that do not elicit much information, and take note of any questions that confuse your participants so you can reword those questions with language that resonates better with older adults.

Also, look for any patterns. Are participants answering with a similar theme or in a similar manner? Try to dig deep when responding to questions that tend to generate similar responses. For example, one of our questions consistently triggered participants to talk about their independence. So we took it a step further by asking them what independence meant to them. Their stories surprised and enlightened us.

Use visual methodologies to broach sensitive subjects

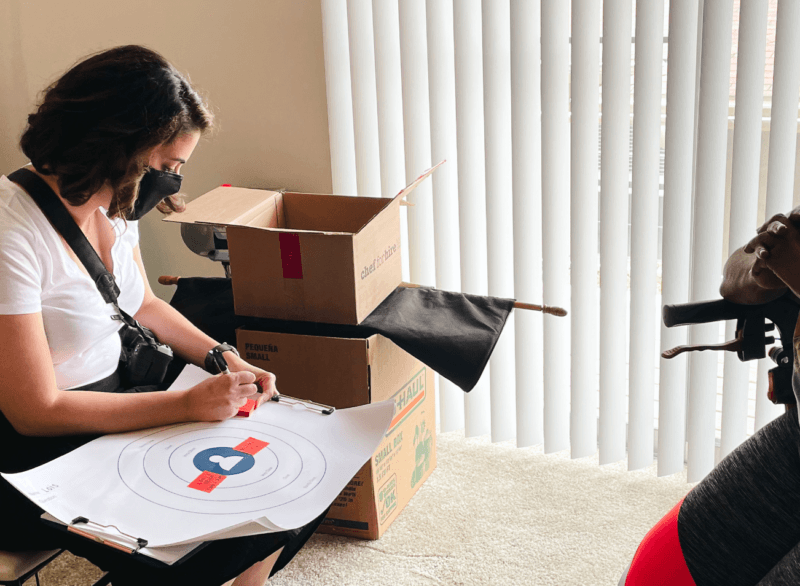

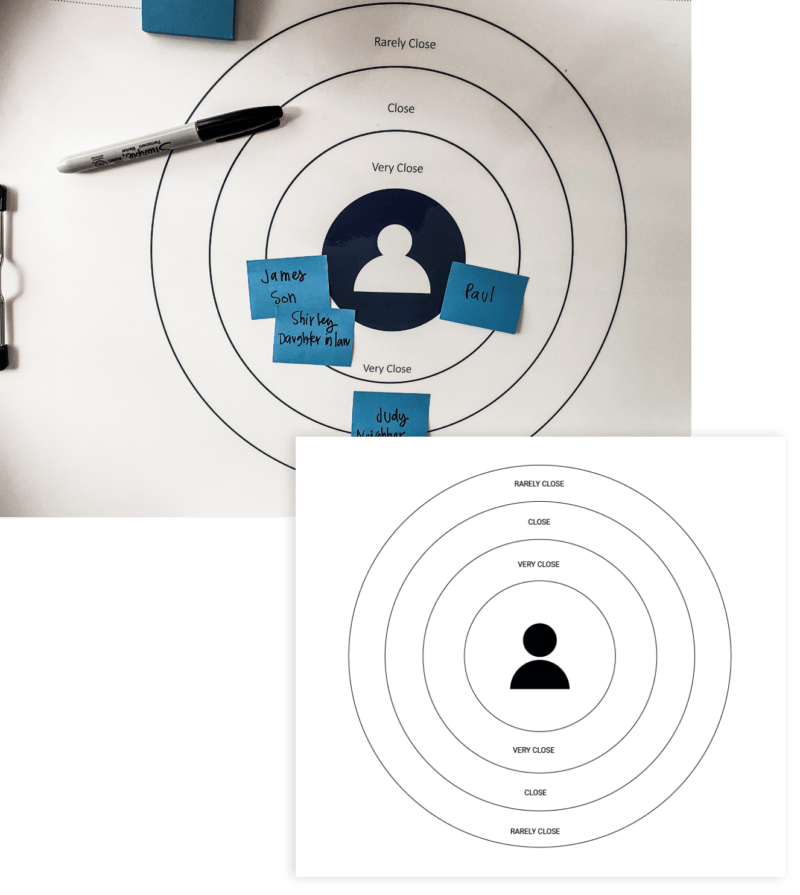

Two important outcomes we hoped to gain from the interview series were to learn about our participants’ care circles and their comfort with technology. Some participants were hesitant to admit that they lacked a care circle or had limitations with technology. To minimize any sensitivity to these subjects, we introduced a visual mapping tool, or relationship map, to help to guide the questioning.

Relationship Map

A relationship map is a diagram that shows relationships or connections applied to an organization or an individual. This type of visual tool can serve as an effective means for broaching sensitive topics and can help ease participants’ inhibitions. In this case, we used relationship maps to encourage participants to share information about their care circles. Not only did relationship mapping help participants relax, but the exercise also generated a lot of excitement. After the interviews, many participants commented about the relationship maps, enthusiastically sharing their experiences and care circle outcomes with their peers.

How does a relationship map work?

Our relationship map showed a bullseye with three layers. The middle of the bullseye represented the participant, while the outer layers represented their connections and level of connectedness with the participant. We asked participants to think about themselves in different scenarios, whether feeling lonely, having a home medical emergency, or going out and having a good time. Then we asked participants to tell us how they would fill out the diagram if they were in the middle of each scenario, including how they would reach a close caregiver or family member and how that individual would help. (See above example.)

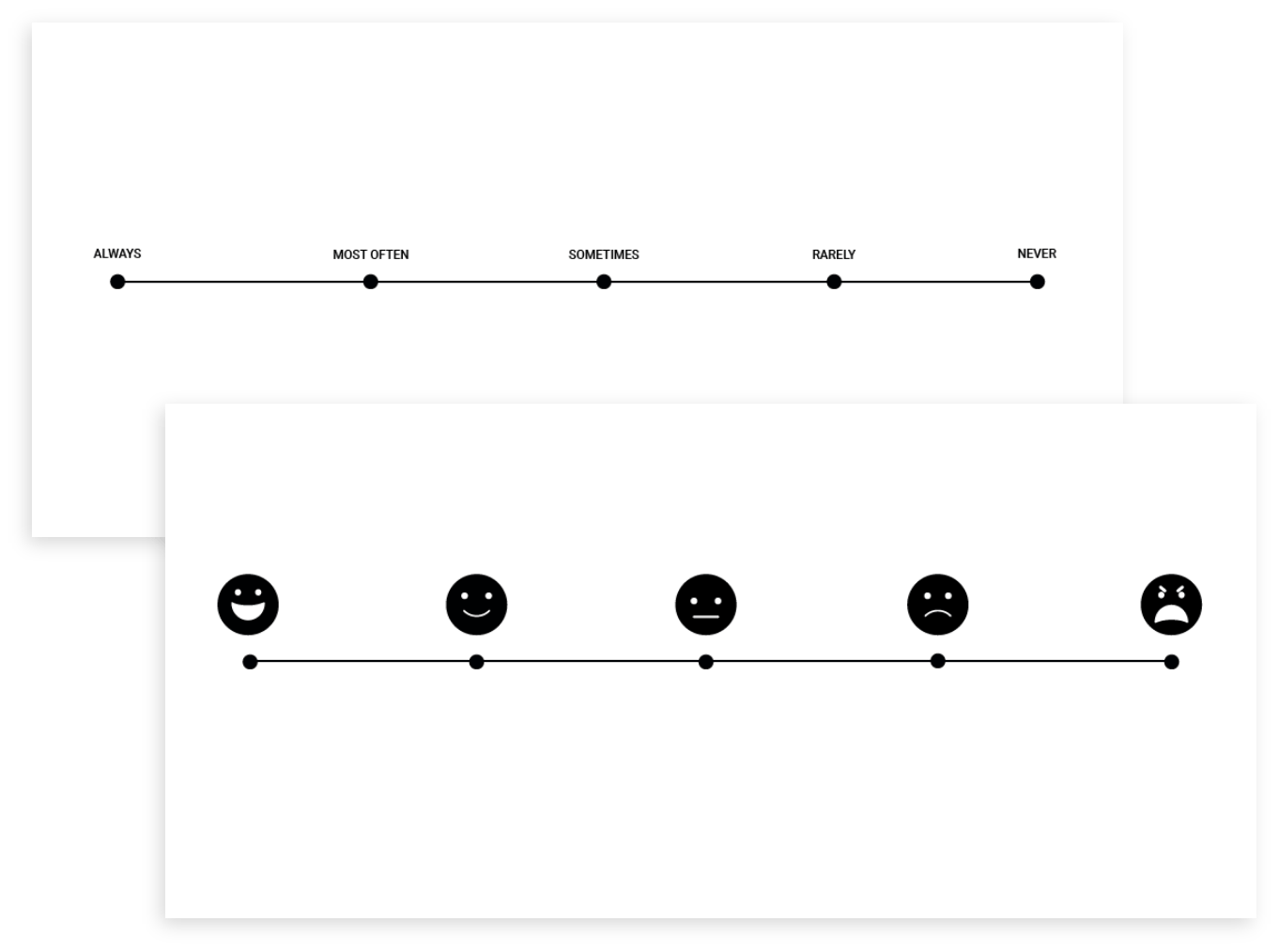

Frequency and emotion scales

Relationship maps played a vital role in our user research and design for older adults. In conjunction with relationship maps, we used frequency and emotion scales to measure how frequently participants use technology tools and how using these tools made them feel. As a conversation starter, we asked participants to tell us about all the electronic devices they use. Next, we asked them to place their usage of those devices on a frequency scale – how often they used those devices and for what purpose. We then provided participants with various sticky notes, each depicting a different technology device, and asked them to post the sticky notes on the emotion scale below.

Conduct a daily debrief with your team

Research studies encompass many moving parts. Multiple researchers interview multiple participants simultaneously. A daily debrief helped align our team. We also updated to our extended team, routinely sending short virtual postcards or Slack messages with daily highlights and other pertinent information. These communications helped document the interview process and served as a valuable reference as we began the analysis process.

User interviews – a gateway to empathy

User interviews are the single most effective method for gathering qualitative information and gaining an in-depth understanding of our users’ needs, motivations, and pain points. In our engagement with CommuniCare, our user interviews helped us establish initial user archetypes that helped inform product strategy decisions, market research, and future feature development designed to address our users’ distinct needs. Our interviews also informed the structure and activities of the co-creation sessions in the study.

By digging deep into our user’s perceptions, activities, and experiences, we could better understand their motivations and challenges and design a product that meets their needs and that they would love.

Usability testing – understanding context & impressions after use

Usability testing is a human-centered methodology used to evaluate a product or service with real people to determine if the product design is intuitive and meets the specific needs of a user. In usability testing, researchers ask users to complete a list of tasks while they observe and document the users’ interactions. We conducted usability testing across two different phases of our research study.

To understand context, we conducted a series of in-person usability tests. We performed a task-based evaluation of the live beta product experience while recording the session on a usability testing platform. As we shared different scenarios with participants, we asked them to think out loud as they interacted with the product and performed various tasks.

Usability testing learning objectives:

- Gather first impressions of the product and its ease of use

- Determine whether users can perform tasks within our product

- Identify problems or pain points that need troubleshooting

- Discover if the product presents any accessibility issues

Usability testing methodology

Our research team performed 30 in-person usability tests, each lasting 45 minutes. Each test with the participant included the product, an observer, and a notetaker. We asked participants to carry out specific tasks during the tests while giving them different contexts. We then asked a series of questions ranging from general questions to very specific questions about their interactions with the product.

Usability testing: What we learned

Though we have plenty of experience in user research, we always pick up valuable insights during each new engagement. During a week of usability testing with older adults, we found it especially important to set clear objectives and communicate with participants throughout the testing phase. Here are some tips we picked up during the planning phase of usability testing.

- Share goals and expectations

- Simplify language

- Simplify tasks

- Use prototypes

Explain your goals and expectations

Starting a usability test can be daunting for anyone. We recorded participants throughout the sessions, both on video and audio. For seniors, this exercise can be particularly anxiety-inducing. Older participants often looked to us for approval to see if they carried out the task properly. Many of our participants wanted to take notes so they could more easily repeat each step when using the product independently.

To put participants at ease, we provided an overview at the beginning of each session, outlining our objectives for the sessions and requesting that they share their thoughts – or think out loud – during the study. We also reminded them that the purpose of the session was for us to simply observe their first interactions with the device rather than to teach them how to use it.

Further, it was important to remind the participants throughout the study that they were not being judged or tested. When they sought our confirmation or approval, we were careful not to respond. Instead, we asked boomerang questions, such as: Do you think that’s the best way to perform that action? Would you have done it another way? What might you do differently?

Simplify your language

In the UX world, we throw around words like prototype, grid, banner, and hamburger. Of course, these terms mean nothing to people outside the field, and they can confuse older adults. To avoid confusion, we created friendlier terms that our participants might better understand. For example, instead of using hamburger, we used the term menu. Using familiar words not only helps participants during usability testing, but user-friendly terminology is also vital during the design phase.

Simplify tasks

Testing several actions simultaneously may be tempting, particularly when using high-fidelity prototypes. We’ve learned to keep it simple, giving our testing participants only one task at a time. It may sound easy to assign a single task to a large group, but it often requires lengthy instructions and can cause confusion among participants. On the other hand, circumstances may call for breaking down a large task into multiple, smaller tasks. Giving participants short-term goals can improve their focus and help reduce the risk of overwhelming them.

It’s also important to keep initial tasks fairly simple so participants have time to adjust to the process and screens. To monitor their understanding, we asked participants to narrate what they saw on each screen. Sometimes they needed reminders. For example, we said things like, Remember to tell me what you are thinking. It’s very important for us to hear your thoughts at this moment.

Using prototypes: Paper prototyping wins the day

To observe how users interact with a product is a critical exercise in user research and design for older adults. A key objective when testing a prototype is to collect participant feedback for product refinement. In the second phase of our study, we wanted to gauge impressions after use. As participants interacted with the prototype, we paused at each screen to ask them specific questions.

During our interviews, some participants withheld their opinions because they feared being perceived as incapable. We concluded that many of the problems that participants faced during the usability testing weren’t due to the product but were due to the participants’ confidence levels.

To adapt to the participants’ needs, we used a different approach with the usability test. First, we showed them a printed version of the prototype, a low-fidelity prototype that we used to demonstrate interactions. The low-fidelity prototype allowed us to test the window flows, validate the concept, and observe how participants would imagine interacting with the product. Participants responded well to this approach. They drew on the paper prototypes and discussed challenges they might face while using the product.

After testing the paper prototype, we then tested participants with an actual pilot app.

We discovered that when participants interacted with the paper prototype first, they had more confidence when it came time to use the pilot app. This initial Interaction with the paper prototype improved participant feedback and generated more questions.

Usability testing is critical to exposing product flaws

Overall, usability testing played a vital role in creating a better user experience for our users. By gathering user feedback on the beta app and prototypes, we uncovered interface and accessibility issues at the beginning of our product’s development and fixed them before releasing the product. Moreover, user feedback helped validate the product’s functionality and appeal to our users.

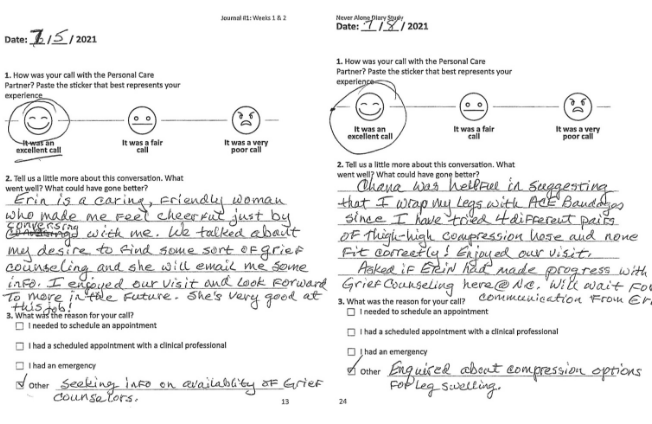

Diary studies – natural use over time

A diary study helps researchers gather personal notes and user feedback about their general experience interacting with a product or service. In our engagement with CommuniCare, we asked participants to document their impressions and interactions with a product for 10 – 12 weeks. We collected the user journals for analysis every two weeks, replacing them with new journals. The diary studies provided pertinent insights into how users interact with a product, from set-up and use to learning.

Diary study learning objectives:

- Gain insights about the overall user experience

- Observe habits that emerge when using the product and how they occur

- Measure level of user engagement and note their primary tasks

- Note user attitudes towards the product, especially any pains points

- Observe changes in behavior or perceptions

- Validate the customer journey

- Uncover any new marketing opportunities

Diary study methodology

In each diary study, we provided participants with interactive journals for 2 – 3 weeks. Each diary study included 2 – 4 exercises about the product stage they were experiencing – from initially learning about the product to the product setup and onboarding, and finally, the use of the product in a real-life context. We also added an activity log query to each diary study so participants could fill out questions about their experiences and provide feedback. We used our MVP to examine participants’ engagement, behavior, habits, gains, pain points, future needs, and motivations.

Diary studies: What we learned

Diary studies are one of the most effective ways to learn about user behavior and a participant’s genuine impressions of a prototype. Diary studies create a safe space for participants to share their experiences and thoughts without fear of judgment, which is particularly important in working with older adults who may not be comfortable with technology.

Offer a variety of communication options

Most people prefer various communication options to choose a method that best suits them. This is particularly true for older adults who may have vision or hearing problems. With this in mind, we offered participants both written and oral formats. Participants shared their responses with our on-site assistant, who entered these comments into a shared Google sheet.

Give clear and concise directions

Provide clear and concise instructions in your diary studies. Because participants will be entering comments without facilitators by their side, they will need clear written instructions.

Consider readability & accessibility

Diary studies are generally provided in a written format, so pick a font size and color that will be easy for older adults to see and read.

Communicate expectations

When seeking input on a prototype, participants must understand what’s expected of them. A prototype, by definition, is something new and innovative, so it’s not surprising that people may feel uncertain about expectations during each activity.

For example, participants grew anxious about expectations in one of our activities called Breakup or Love Letter. In the activity, we asked participants to write a letter to the software that was communicating either a breakup with the product or a love letter about it. Some of our participants were hesitant to write a breakup letter because they feared a breakup would end their role in the study. We needed to reiterate the point of the activity, carefully restating objectives and explaining how their feedback would be used.

Diary studies are an efficient way to collect qualitative data

While diary studies can’t provide a complete picture of a user’s impressions, they are a critical tool in user research because they offer a simple way to obtain longitudinal information about a user’s impressions, preferences, and behaviors over time – and from multiple participants simultaneously.

In our engagement with CommuniCare, diary studies provided us with continual feedback during the initial release of the pilot program, allowing us to identify pain points that users’ experienced while interacting with the app. These studies also shed light on user questions about the product, their assumptions, and how well users understood the app’s multiple uses and benefits – another critical element in user research and design for older adults.

Co-creation workshops – impressions after use

A co-creation workshop is a space for collaboration in which users and researchers participate together in the creation process of a new product or service. In our engagement with CommuniCare, we conducted a co-creation workshop that included all study participants and a series of smaller workshops broken down by archetype.

Workshop learning objectives

- Observe initial impressions of the product

- Gather user questions

- Identify opportunities to improve

- Note user behavior & preferences according to archetypes

Workshop methodology

We conducted seven workshops in one week. In the first workshop, we introduced users to the idea of co-creation and showed the participants our progress with the product and its updates. We then grouped participants into different archetype profiles and conducted five small workshops, in which we co-created around different themes like:

- Security & trust

- Vitality & independence

- Partnership & transitions

- Caregivers & family

- Community & friendships

Workshops: What we learned

During the workshop phase of the study, we were careful to maintain clear objectives while also allowing for some flexibility. Throughout the workshops, we focused on clear and continual communication and ease of accessibility to our workshop spaces and activities.

- Build rapport

- Be prepared to pivot

- Be intentional

- Develop a workshop outline

- Use familiar language

- Consider accessibility

- Plan for memory and learning challenges

Build a rapport

To communicate effectively with older adults, it’s critical to build a face-to-face rapport. For example, during our pilot, we continually kept in contact with participants, sending thank you notes and simply touching base with them every so often. These little touchpoints helped build trust and a willingness to engage more deeply with us. As a result, when conducting co-creation workshops, our users felt they were heard and that their ideas and feedback brought value to the process. We reinforced the idea that their comments and feedback were going to help shape a product feature while also emphasizing how much we valued their time and effort.

Be flexible and prepared to pivot during workshop activities

We’ve said it before and can’t say it enough. Flexibility is critical. In our studies, we continually needed to observe and adapt. When participants struggled with an activity, we were prepared to pivot quickly, carefully maintaining focus on the activity goal, yet ready with backup plans if activities needed to be modified.

For example, we initiated an activity involving movement around the room. But when we saw that our participants were having trouble moving, we quickly modified the activity to allow participants to respond from their seats and hold up answers on sticky notes.

Additionally, we took note of the activities that participants enjoyed the most. For example, in our first small workshop, we performed a role-playing exercise in which participants acted out different scenarios. Our older adults particularly loved that activity, so we adapted our smaller workshops to include various role-playing activities as well.

Be intentional

Workshop activities need to be well-organized and carried out quickly. If you deviate from the original plan, be sure to appear intentional and decisive.

Develop a workshop outline and agenda

During our planning process, we drafted an outline for each workshop, correlating each activity with a specific goal. Each activity within the plan included facilitator instructions, objectives, and activity duration. Because participants often prefer certain activities over others, or move through an activity more quickly than expected, be prepared to adjust time frames for activities. For example, we had one discussion activity that was particularly exciting to many participants. During the activity, they really opened up and expressed an eagerness to share. The conversation flowed so well that we decided to modify and abbreviate the following two activities.

Use language that’s familiar to your audience

Before each workshop, we created and distributed pre-printed cards with questions for our participants to consider throughout the workshops. Initially, our questions were too technical, which flustered our audience. We then had to go back and rewrite several questions using more familiar language.

When composing questions, use language that is accessible to older adults. Along with each question, you might want to provide a sample answer just in case participants needed some guidance.

Consider Accessibility

During workshops, it’s important to consider an audience’s accessibility issues. For example, we have found that many older adults cannot easily read deck presentations or hear voices over a microphone. Providing a variety of formats can ensure that participants will receive information in a way best suited for them.

Accessibility tips:

- Print out presentation decks before the workshop

- Create small group settings to reduce noise. If a large group is necessary, assign a facilitator for individuals with hearing problems.

- Don’t fill the room with chairs. Rooms should be wheelchair accessible and clear of any trip hazards.

Plan for memory and learning challenges

When developing workshops, each workshop should have a clear set of goals and build on the previous workshop. When working with older adults, we’ve learned that as we move on to each new workshop, many participants disregard answers from the previous activity, in effect hitting a reset button and starting over.

To ensure continuity between workshops, we used an outline as a framework and defined clear objectives with each activity. Sticky notes were also helpful. We left blank areas for sticky notes so participants could fill in what they’d learned from each activity. Then, as we moved through each new workshop, we pointed them to their sticky notes from the previous workshop.

Co-creating with older adults

No matter how much you prepare for a co-creation workshop, the most important component for a successful workshop is emotional safety. Have you pulled in the right people and created an environment in which your participants feel they can share and not be judged? The most basic principle of a successful workshop is to draw everyone into the creative process and ensure that everyone feels valued and heard.

In our engagement with CommuniCare, our co-creation sessions inspired participants to open up in new and dramatic ways, and as a result, we discovered a new service opportunity for the product, moving us to rethink and reprioritize features on our product development and custom software development roadmap.