How a Minimum Viable Product helped Huddle find a new market

Recently, Huddle Tickets raised $11 million to fund their expansion of GoFan, a mobile ticketing solution for high school events. The app started with a minimum viable product that was developed in 75 days, allowing them to go to market quickly and validate their initial idea.

GoFan is poised to be the market leader in digital ticketing for K-12 events, but just a few years ago, the idea would have never gotten off the ground.

It would have required at least a year’s worth of market research, planning and development, not to mention a great deal of money, before it ever got into users’ hands. And after all that, there would have been a strong chance that the app would not fit with the market and have gained widespread acceptance.

The problem would not necessarily have been with the idea itself, or with the available technology, or even consumer preference. It’s that it would have taken too much time and money for it to be launched.

In short, it would have been too risky.

But creating a minimum viable product (MVP) significantly reduces that risk, making it easier and less expensive for companies to take their idea to market.

Most importantly, the MVP helps companies move from idea to product fast with a primary value proposition. In the case of Huddle’s GoFan app, it was just 75 days.

From paper to digital

Huddle, Inc., is one of the nation’s leading providers of paper tickets for K-12 events. Any time a school sells tickets to an event — sports games, concerts, plays — there’s a good chance those tickets came from Huddle.

Their business model centered on printing promotions from local businesses on the back of the tickets. The tickets themselves were essentially a medium through which Huddle sold advertising. Selling the tickets, distributing them, and validating them at the events was the responsibility of the schools.

But Huddle had been working with schools for many years. They knew their industry and their customer base well, and they could sense that things might change. Digital ticketing was becoming ubiquitous in almost every other event and venue, including college and professional sports, concerts, and even movies. Huddle knew digital ticketing could make its way to school events, which would disrupt their business model.

But Huddle didn’t want to be on the receiving end of the disruption. According to Huddle CEO Joey Thacker, they wanted to be the technological leaders in their space, not the followers or the also-rans. “(W)e wanted to own the disruption,” he said.

Validating an Idea, Fast

When Huddle came to us, they had a great idea and a hunch that it could turn into something big. They wanted to run an experiment to see if and how mobile digital ticketing would work for high school football games before investing significant resources.

That’s really what an MVP is. It’s a method to test an idea by quickly getting it into users’ hands, and learning through user behavior and feedback what works, what doesn’t, and what might work in the next iteration.

The key word above is “quickly.” When we started, it was August, and the high school football season was already getting into gear. If they weren’t able to run their test in the approaching season, they would have had to wait another year, and that might have effectively killed the project.

Under those circumstances, the temptation might be to gather some developers in a room and have them start writing code. But the first, and most important part of the minimum viable product process is to fully understand what the problem we’re trying to solve is.

To do that, we start with our destination workshops, in which we discuss the project, the different user groups, the problems they have, and how they would likely use the product. We talk about the optimal path users will take, as well as any exceptions. The goal of this process is to determine the primary use case for the product and use that as the foundation upon which the MVP will be built.

In the case of digital ticketing for high school events, there were a lot of questions that needed to be answered. Purchasing tickets for high school football games has traditionally been a cash-based process, with tickets being sold only the day of or the day before the event.

We needed to think through what a new process would look like for users. The process would be very different than what people were used to. They would buy tickets online, using credit cards, rather than on-site with cash. Parents would conceivably purchase tickets and transfer them to their kids. Students who bought tickets on their own would have to follow a new process. Would users adopt this new process, and what would their path through the app look like?

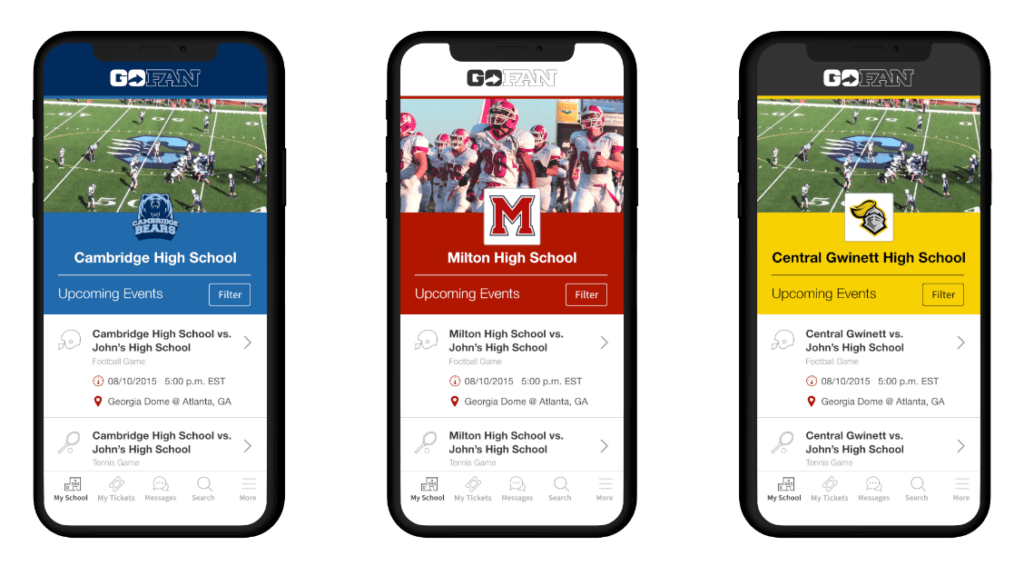

We also thought about the product from the school’s perspective, as they represented a different, but just as important, user group. How would the product affect them in areas like accepting payment and validating tickets at the event? Also, how would the product project the school’s image and brand?

After this phase of the MVP, we came away with a Product Blueprint, a shared vision of what the product would be, the problems it would solve, and how people would use it. The blueprint focused on a very specific user scenarios, with a few exceptions, that would be addressed in the MVP’s first iteration.

Reducing Risk

The next phase of the minimum viable product process was to build a mobile app based on the blueprint. It needed to be done fast, and one of the benefits inherent to MVPs is speed.

Because we were focusing only on a few specific user scenarios, our developers and user experience designers were able to hone in on solving those specific problems. Any features that didn’t solve those problems were left out of the MVP.

One of the key features that needed to be included in the minimum viable product was a scanning capability for validating tickets at the gate. Because schools would not have professional 3D scanners, like what are used at major sports venues, we had to include a 2D scanning feature that used a smartphone’s camera.

The 3D scanning would come later, but to test the product, it had to be possible for school ticket takers to scan tickets using their own phones.

The MVP process also lets us focus our development effort on the aspects of the product that made it unique, and gave it a compelling user experience. Off-the-shelf technologies were used for any functions that were necessary but not differentiating, such as processing credit cards.

This approach is crucial to the MVP process. It takes unnecessary cost and development time out of the equation, helping us build a product faster and less expensively.

By October, the minimum viable product was ready to launch. Huddle offered it to six high schools for a single football weekend. The results were shockingly good.

GoFan passed its first test with high marks. Among the learnings Huddle gleaned from this test were:

- Ticket buyers — parents and students — were thrilled to not have to wait in line at a specific time to buy tickets.

- Schools were surprised to be able to validate tickets at the gate using smart phones.

- Schools appreciated the ability to better manage revenue from ticket sales, having the money electronically deposited into an account rather than sitting in a cash box.

The mobile app successfully solved several user problems they had become accustomed to living with. More importantly, it validated to Huddle that they had a good idea on their hands, and that it was worthwhile to pursue it further.

Success, no matter the result

Our usual minimum viable product process is 90 days. Huddle had an accelerated process, and we were able to launch the product in 75 days.

By all but eliminating the risk associated with developing a new digital product, the MVP gave Huddle the confidence they needed to further invest in GoFan. It formed the foundation for what would become a successful product and a new business model for Huddle.

Before long, they were able to surpass, and ultimately acquire, a competitor who had an 18-month head start.

Of course, no one knew for sure how the MVP would turn out. We all felt positive, but the results might have been different. Users could have simply not adopted the product, or the technology might have been too cumbersome. Or they might have rejected certain features and demanded other ones.

Users might also have favored the desktop or mobile web versions of the product, eschewing the mobile app. Another outcome might have involved how the schools handled digital and paper tickets, and if the two could be integrated into one system.

All of that and more was possible. But if that had happened, if the GoFan MVP was rejected, it still would have been a success.

Taking the MVP approach meant Huddle had little risk exposure. We built their solution using Ionic Framework, which allowed us to build all three platforms (desktop, mobile web, mobile app) at a low cost, in turn making it possible to test to see which platforms users would prefer. Had we built only a mobile app, it might have been difficult to convince people to download it, and we would have received very little feedback on the product.

More importantly, Huddle sensed a looming change in their industry, and they wanted to be on the forefront of it. If the change they sensed was not imminent, conducting a test through the MVP would have prevented them from spending untold millions on developing a product that ultimately was doomed to fail.

The minimum viable product allowed them to get their product to market in a short time and at minimal investment. At a minimal risk, they were able to own the disruption in their industry, and stake out a leadership position.

Are you ready to disrupt your industry? Let’s talk.